Igor Stravinsky

Oedipus Rex

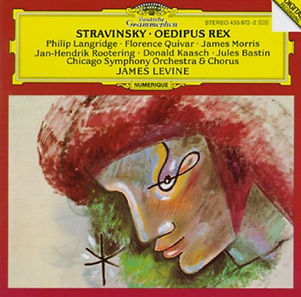

Igor STRAVINSKY: "Oedipus Rex"

Lajos Kozma ... Œdipus (tenor)

Tatiana Troyanos ... Jocasta (mezzo-soprano)

Frans Crass ... Créon (bass-baritone)

Luigi Roni ... Tirésias (basso)

Ferdinando Jacopucci ... Shepherd (tenor)

Giancarlo Sbragia ... narrator (speaking role)

Theban chorus ... Men's Chorus

Orchestra Sinfonica e Coro di Roma della RAI

Claudio Abbado, conductor

Auditorio Foro Italico, Roma, 8 February 1969)

Oedipus rex is an "Opera-oratorio after Sophocles" by Igor Stravinsky, scored for orchestra, speaker, soloists, and male chorus. The libretto, based on Sophocles's tragedy, was written by Jean Cocteau in French and then translated by Abbé Jean Daniélou into Latin; the narration, however, is performed in the language of the audience.

Oedipus rex was written towards the beginning of Stravinsky's neoclassical period, and is considered one of the finest works from this phase of the composer's career. He had considered setting the work in Ancient Greek, but decided ultimately on Latin: in his words "a medium not dead but turned to stone.

Oedipus rex is sometimes performed in the concert hall as an oratorio, similarly to its original performance in the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt in Paris on 30 May 1927, and at its American premiere the following year, given by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the Harvard Glee Club.

It has also been presented on stage as an opera, the first such performance being at the Vienna State Opera on 23 February 1928. It was subsequently presented three times by the Santa Fe Opera in 1960, 1961, and 1962 with the composer in attendance. In January 1962 it was performed in Washington, D.C., by the Opera Society of Washington (now the Washington National Opera) with the composer conducting.

In 1960 at Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London, a production by Colin Graham, directed by Michel Saint-Denis, conducted by Colin Davis and designed by Abd’Elkader Farrah. Oedipus was sung by Australian tenor Ronald Dowd with actor Michael Hordern as narrator. Although the performance's narration was in English, the company moved from its normal English-language practice and the singing remained in the original Latin.

A production directed by Julie Taymor starring Philip Langridge, Jessye Norman, Min Tanaka, and Bryn Terfel was performed at the Saito Kinen Festival Matsumoto in Japan in 1992 and filmed by Taymor for television.

Many insights to this opera are found in Leonard Bernstein's analysis of it in his sixth and last Norton lecture from 1973. Bernstein stated that Oedipus Rex is the most "awesome product" of Stravinsky's neoclassical period. Much of the music borrows techniques from past classical styles and from popular styles of the day as well. However, Stravinsky purposely mismatches the text subjects (in Latin) with its corresponding musical accompaniment.

Igor Stravinsky "Oedipus Rex."

Leonard Bernstein Conducting.

Stravinsky's great opera-oratorio

Recorded in London, August 2014.

Cast

Oedipus – Allan Clayton

Jocasta – Hilary Summers

Creon – Juha Uusitalo

Tiresias – Brindley Sherratt

Messenger – Duncan Rock

Shepherd – Samuel Boden

Speaker – Rory Kinnear

Sakari Oramo - conductor

BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. BBC Singers.

Igor Stravinsky - Jean Cocteau - Oedipus Rex

Opéra Oratorio Stravisky

Historical Recording of the first performance at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées

Léopold Simoneau, Bernard Cottret, George Abdoun, Gérard Serkoyan, Eugenia Zareska, Michel Hamel.

Jean Cocteau, récitant

Orchestre National, Choeur de la RDF sous la direction de Stravinsky

Roles

OEDIPUS REX

Opera-oratorio by Igor Stravinsky.

The libretto, based on Sophocles's tragedy,

was written by Jean Cocteau in French and

then translated by Abbé Jean Daniélou into Latin.

Oedipus, king of Thebes

Jocasta, his wife & mother

Creon, Jocasta's brother

Tiresias, soothsayer

Shepherd (herder)

Messenger

Narrator (speaker)

Men's chorus

Time: Ancient Greek

Place: Thebes

Premiere Cast, 30 May 1927 (Conductor: Igor Stravinsky)

Character

Oedipus:

Tenor. Son of King Laius and Queen Jocasta, and now husband of Jocasta. Considered to be the son of and heir to King Polybus' throne. Oedipus promises to find the murderer of King Laius, and thus rescue Thebes from the plague. His wife tells him that Laius was killed by thieves at a crossroads. Frightened, Oedipus confesses to her that years ago he killed an old man at a crossroads. A messenger announces the death of King Polybus and tells Oedipus he was not really the king's son. He was found on a mountain and raised by Polybus, but was the son of Laius and Jocasta. Realizing he has killed his own father and married his mother, Oedipus blinds himself with Jocasta’s brooch and is sent into exile by his people. Created (1927) by Stephane Belina-Skupievsky.

Jocasta:

Mezzo-soprano. Sister of Creon, and widow of Laius, the late King of Thebes, and now wife of Oedipus. She has consulted the Oracle who has told her that Laius was killed by his son, but she knows Laius was killed by thieves at a crossroads. Oedipus confesses that, in the past, he killed an old man at a crossroads. It gradually becomes apparent that he killed his own father, and then married his mother. Overcome, Jocasta kills herself. Created ( 1927 ) by Hélène Sadoven.

Creon:

Bass‐baritone. Brother of Oedipus’ wife, Jocasta. Accused by Oedipus of plotting to seize the throne of Thebes. Created ( 1927 ) by Georges Lanskoy (who also created the Messenger—the two roles are usually sung by the same artist).

Tiresias:

Bass. The blind Seer who refuses to help Oedipus discover the truth about the death of King Laius. He is accused by Oedipus of plotting to seize the throne of Thebes. Created ( 1927 ) by Kapiton Zaporojetz .

Messenger:

Bass-baritone. Brings news of the death of King Polybus and of Oedipus’ true lineage. Created ( 1927 ) by Georges Lanskoy (who also created Creon)

Speaker:

Spoken. Announces that a story will unfold which will reveal the truth about Oedipus. Created (1927) by Pierre Brasseur.

Synopsis

Michael Levine - designer

ACT I

The Narrator greets the audience, explaining the nature of the drama they are about to see, and setting the scene: Thebes is suffering from a plague, and the men of the city lament it loudly. Oedipus, king of Thebes and conqueror of the Sphinx, promises to save the city. Creon, brother-in-law to Oedipus, returns from the oracle at Delphi and declaims the words of the gods: Thebes is harboring the murderer of Laius, the previous king. It is the murderer who has brought the plague upon the city. Oedipus promises to discover the murderer and cast him out. He questions Tiresias, the soothsayer, who at first refuses to speak. Angered at this silence, Oedipus accuses him of being the murderer himself. Provoked, Tiresias speaks at last, stating that the murderer of the king is a king. Terrified, Oedipus then accuses Tiresias of being in league with Creon, whom he believes covets the throne. With a flourish from the chorus, Jocasta appears.

ACT II

Jocasta calms the dispute by telling all that the oracles always lie. An oracle had predicted that Laius would die at his son's hand, when in fact he was murdered by bandits at the crossing of three roads. This frightens Oedipus further: he recalls killing an old man at a crossroads before coming to Thebes. A messenger arrives: King Polybus of Corinth, whom Oedipus believes to be his father, has died. However, it is now revealed that Polybus was only the foster-father of Oedipus, who had been, in fact, a foundling. An ancient shepherd arrives: it was he who had found the child Oedipus in the mountains. Jocasta, realizing the truth, flees. At last, the messenger and shepherd state the truth openly: Oedipus is the child of Laius and Jocasta, killer of his father, husband of his mother. Shattered, Oedipus leaves. The messenger reports the death of Jocasta: she has hanged herself in her chambers. Oedipus breaks into her room and puts out his eyes with her pin. He departs Thebes forever as the chorus at first vents their anger, and then mourns the loss of the king they loved.

Greek Mythology

Oedipus Rex, also known by its Greek title, Oedipus Tyrannus, or Oedipus the King, is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles that was first performed around 429 BC. Originally, to the ancient Greeks, the title was simply Oedipus (Οἰδίπους), as it is referred to by Aristotle in the Poetics. It is thought to have been renamed Oedipus Tyrannus to distinguish it from another of Sophocles' plays, Oedipus at Colonus. In antiquity, the term “tyrant” referred to a ruler, but it did not necessarily have a negative connotation.

Of his three Theban plays that have survived, and that deal with the story of Oedipus, Oedipus Rex was the second to be written. However, in terms of the chronology of events that the plays describe, it comes first, followed by Oedipus at Colonus and then Antigone.

Prior to the start of Oedipus Rex, Oedipus has become the king of Thebes while unwittingly fulfilling a prophecy that he would kill his father, Laius (the previous king), and marry his mother, Jocasta (whom Oedipus took as his queen after solving the riddle of the Sphinx). The action of Sophocles' play concerns Oedipus' search for the murderer of Laius in order to end a plague ravaging Thebes, unaware that the killer he is looking for is none other than himself. At the end of the play, after the truth finally comes to light, Jocasta hangs herself while Oedipus, horrified at his patricide and incest, proceeds to gouge out his own eyes in despair.

Bénigne Gagneraux, The Blind Oedipus Commending his Children to the Gods

Oedipus, King of Thebes, sends his brother-in-law, Creon, to ask advice of the oracle at Delphi, concerning a plague ravaging Thebes. Creon returns to report that the plague is the result of religious pollution, since the murderer of their former king, Laius, has never been caught. Oedipus vows to find the murderer and curses him for causing the plague.

Oedipus summons the blind prophet Tiresias for help. When Tiresias arrives he claims to know the answers to Oedipus's questions, but refuses to speak, instead telling him to abandon his search. Oedipus is enraged by Tiresias' refusal, and verbally accuses him of complicity in Laius' murder. Outraged, Tiresias tells the king that Oedipus himself is the murderer ("You yourself are the criminal you seek"). Oedipus cannot see how this could be, and concludes that the prophet must have been paid off by Creon in an attempt to undermine him. The two argue vehemently, as Oedipus mocks Tiresias' lack of sight, and Tiresias in turn tells Oedipus that he himself is blind. Eventually Tiresias leaves, muttering darkly that when the murderer is discovered he shall be a native citizen of Thebes, brother and father to his own children, and son and husband to his own mother.

Creon arrives to face Oedipus's accusations. The King demands that Creon be executed; however, the chorus persuades him to let Creon live. Jocasta enters and attempts to comfort Oedipus, telling him he should take no notice of prophets. As proof, she recounts an incident in which she and Laius received an oracle which never came true. The prophecy stated that Laius would be killed by his own son; however, Jocasta reassures Oedipus by her statement that Laius was killed by bandits at a crossroads on the way to Delphi.

The mention of this crossroads causes Oedipus to pause and ask for more details. He asks Jocasta what Laius looked like, and Oedipus suddenly becomes worried that Tiresias's accusations were true. Oedipus then sends for the one surviving witness of the attack to be brought to the palace from the fields where he now works as a shepherd.

Jocasta, confused, asks Oedipus what the matter is, and he tells her. Many years ago, at a banquet in Corinth, a man drunkenly accused Oedipus of not being his father's son. Oedipus went to Delphi and asked the oracle about his parentage. Instead of answers he was given a prophecy that he would one day murder his father and sleep with his mother. Upon hearing this he resolved to leave Corinth and never return. While traveling he came to the very crossroads where Laius was killed, and encountered a carriage which attempted to drive him off the road. An argument ensued and Oedipus killed the travelers, including a man who matches Jocasta's description of Laius. Oedipus has hope, however, because the story is that Laius was murdered by several robbers. If the shepherd confirms that Laius was attacked by many men, then Oedipus is in the clear.

A man arrives from Corinth with the message that Oedipus's father has died. Oedipus, to the surprise of the messenger, is made ecstatic by this news, for it proves one half of the prophecy false, for now he can never kill his father. However, he still fears that he may somehow commit incest with his mother. The messenger, eager to ease Oedipus's mind, tells him not to worry, because Merope was not in fact his real mother.

It emerges that this messenger was formerly a shepherd on Mount Cithaeron, and that he was given a baby, which the childless Polybus then adopted. The baby, he says, was given to him by another shepherd from the Laius household, who had been told to get rid of the child. Oedipus asks the chorus if anyone knows who this man was, or where he might be now. They respond that he is the same shepherd who was witness to the murder of Laius, and whom Oedipus had already sent for. Jocasta, who has by now realized the truth, desperately begs Oedipus to stop asking questions, but he refuses and Jocasta runs into the palace.

When the shepherd arrives Oedipus questions him, but he begs to be allowed to leave without answering further. However, Oedipus presses him, finally threatening him with torture or execution. It emerges that the child he gave away was Laius's own son, and that Jocasta had given the baby to the shepherd to secretly be exposed upon the mountainside. This was done in fear of the prophecy that Jocasta said had never come true: that the child would kill his father.

Everything is at last revealed, and Oedipus curses himself and fate before leaving the stage. The chorus laments how even a great man can be felled by fate, and following this, a servant exits the palace to speak of what has happened inside. When Jocasta enters the house, she runs to the palace bedroom and hangs herself there. Shortly afterward, Oedipus enters in a fury, calling on his servants to bring him a sword so that he might cut out his mother's womb. He then rages through the house, until he comes upon Jocasta's body. Giving a cry, Oedipus takes her down and removes the long gold pins that held her dress together, before plunging them into his own eyes in despair.

A blind Oedipus now exits the palace and begs to be exiled as soon as possible. Creon enters, saying that Oedipus shall be taken into the house until oracles can be consulted regarding what is best to be done. Oedipus's two daughters (and half-sisters), Antigone and Ismene, are sent out, and Oedipus laments their having been born to such a cursed family. He asks Creon to watch over them and Creon agrees, before sending Oedipus back into the palace.

On an empty stage the chorus repeat the common Greek maxim, that no man should be considered fortunate until he is dead.

Oedipus explains the riddle of the Sphinx,

by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, c. 1805

Oedipus (UK: /ˈiːdɪpəs/, US: /ˈiːdəpəs, ˈɛdə-/; Greek: Οἰδίπους Oidípous meaning "swollen foot") was a mythical Greek king of Thebes. A tragic hero in Greek mythology, Oedipus accidentally fulfilled a prophecy that he would end up killing his father and marrying his mother, thereby bringing disaster to his city and family.

The story of Oedipus is the subject of Sophocles' tragedy Oedipus Rex, which was followed by Oedipus at Colonus and then Antigone. Together, these plays make up Sophocles' three Theban plays. Oedipus represents two enduring themes of Greek myth and drama: the flawed nature of humanity and an individual's role in the course of destiny in a harsh universe.

In the most well-known version of the myth, Oedipus was born to King Laius and Queen Jocasta. Laius wished to thwart a prophecy, so he left Oedipus to die on a mountainside. However, the baby was found by shepherds and raised by King Polybus and Queen Merope as their own. Oedipus learned from the oracle at Delphi of the prophecy that he would end up killing his father and marrying his mother but, unaware of his true parentage, believed he was fated to murder Polybus and marry Merope, so left for Thebes. On his way he met an older man and quarrelled, and Oedipus killed the stranger. Continuing on to Thebes, he found that the king of the city (Laius) had been recently killed, and that the city was at the mercy of the Sphinx. Oedipus answered the monster's riddle correctly, defeating it and winning the throne of the dead king – and the hand in marriage of the king's widow, and (unbeknownst to him) his mother Jocasta.

Years later, to end a plague on Thebes, Oedipus searched to find who had killed Laius, and discovered that he himself was responsible. Jocasta, upon realizing that she had married both her own son, and her husband's murderer, hanged herself. Oedipus then seized two pins from her dress and blinded himself with them.

The “Oedipus Effect," as named by philosopher of Science, Karl Popper, is an adverse outcome of a 'Self-fulfilling Prophecy' (sociologist Robert Merton, 1948), a self-defeating prophecy. Popper concluded his definition in 1957, where he wrote; ‘exact and detailed scientific social predictions are therefore impossible’.

The legend of Oedipus has been retold in many versions, and was used by Sigmund Freud to name and give mythic precedent to the Oedipus complex.

Oedipus Separating from Jocasta by Alexandre Cabanel.

In Greek mythology, Jocasta, also known as Iocaste, was a daughter of Menoeceus, a descendant of the Spartoi, and Queen consort of Thebes. She was the wife of first Laius, then of their son Oedipus, and both mother and grandmother of Antigone, Eteocles, Polynices and Ismene. She was also sister of Creon and mother-in-law of Haimon.

After his abduction and rape of Chrysippus, Laius married Jocasta. Laius received an oracle from Delphi which told him that he must not have a child with his wife, or the child would kill him and marry her; in another version, recorded by Aeschylus, Laius is warned that he can only save the city if he dies childless. One night, Laius became drunk and fathered Oedipus with Jocasta.

Jocasta handed the newborn infant over to Laius. Jocasta or Laius pierced and pinned the infant's ankles together. Laius instructed his chief shepherd, a slave who had been born in the palace, to expose the infant on Mount Cithaeron. Laius's shepherd took pity on the infant and gave him to another shepherd in the employ of King Polybus of Corinth. Childless, Polybus and his Queen, Merope (according to Sophocles, or Periboea according to Pseudo-Apollodorus), raised the infant to adulthood.

Oedipus grew up in Corinth under the assumption that he was the biological son of Polybus and his wife. Hearing rumors about his parentage, he consulted the Delphic Oracle. Oedipus was informed by the Oracle that he was fated to kill his father and to marry his mother. Fearing for the safety of the only parents known to him, Oedipus fled from Corinth before he could commit these sins. During his travels, Oedipus encountered Laius on the road. After a heated argument regarding right-of-way, Oedipus killed Laius, unknowingly fulfilling the first half of the prophecy. Oedipus continued his journey to Thebes and discovered that the city was being terrorized by the sphinx. Oedipus solved the sphinx's riddle, and the grateful city elected Oedipus as their new king; Oedipus accepted the throne and married Laius' widowed queen Jocasta, fulfilling the second half of the prophecy. Jocasta bore him four children: two girls, Antigone and Ismene, and two boys, Eteocles and Polynices.

Differing versions exist concerning the latter part of Jocasta's life. In the version of Sophocles, when his city was struck by a plague, Oedipus learned that it was divine punishment for his patricide and incest. Hearing this news, Jocasta hanged herself. But in the version told by Euripides, Jocasta endured the burden of disgrace and continued to live in Thebes, and committing suicide after her sons kill one another in a fight for the crown. In both traditions Oedipus gouges out his eyes; Sophocles has Oedipus go into exile with his daughter Antigone, but Euripides and Statius have him residing within Thebes' walls during the war between Eteocles and Polynices.

Creon is a figure in Greek mythology best known as the ruler of Thebes in the legend of Oedipus. He had four sons and three daughters with his wife, Eurydice (sometimes known as Henioche): Henioche, Pyrrha, Megareus (also called Menoeceus), Lycomedes and Haimon. Creon and his sister, Jocasta, were descendants of Cadmus and of the Spartoi. He is sometimes considered to be the same person who purified Amphitryon of the murder of his uncle Electryon and father of Megara, first wife of Heracles.

Creon figures prominently in the plays Oedipus Rex and Antigone, written by Sophocles.

In Oedipus Rex, Creon is a brother of queen Jocasta, the wife of King Laius as well as Oedipus. Laius, a previous king of Thebes, had given the rule to Creon while he went to consult the oracle at Delphi. During Laius's absence, the Sphinx came to Thebes. When word came of Laius's death, Creon offered the throne of Thebes as well as the hand of his sister (and Laius' widow) Jocasta, to anyone who could free the city from the Sphinx. Oedipus answered the Sphinx's riddle and married Jocasta, unaware that she was his mother. Over the course of the play, as Oedipus comes closer to discovering the truth about Jocasta, Creon plays a constant role close to him. When Oedipus summons Tiresias to tell him what is plaguing the city and Tiresias tells him that he is the problem, Oedipus accuses Creon of conspiring against him. Creon argues that he does not want to rule and would, therefore, have no incentive to overthrow Oedipus. However, when the truth is revealed about Jocasta, and Oedipus requests to be exiled, it is Creon who grants his wish and takes the throne in his stead.

In Greek mythology, Tiresias (/taɪˈriːsiəs/; Greek: Τειρεσίας, Teiresias) was a blind prophet of Apollo in Thebes, famous for clairvoyance and for being transformed into a woman for seven years. He was the son of the shepherd Everes and the nymph Chariclo. Tiresias participated fully in seven generations in Thebes, beginning as advisor to Cadmus himself.

Tiresias and Thebes

Tiresias appears as the name of a recurring character in several stories and Greek tragedies concerning the legendary history of Thebes. In The Bacchae, by Euripides, Tiresias appears with Cadmus, the founder and first king of Thebes, to warn the current king Pentheus against denouncing Dionysus as a god. Along with Cadmus, he dresses as a worshiper of Dionysus to go up the mountain to honor the new god with the Theban women in their Bacchic revels.

In Sophocles' Oedipus Rex, Oedipus, the king of Thebes, calls upon Tiresias to aid in the investigation of the killing of the previous king Laius. At first, Tiresias refuses to give a direct answer and instead hints that the killer is someone Oedipus really does not wish to find. However, after being provoked to anger by Oedipus' accusation first that he has no foresight and then that Tiresias had a hand in the murder, he reveals that in fact it was Oedipus himself who had (unwittingly) committed the crime. Outraged, Oedipus throws him out of the palace, but then afterwards realizes the truth.

Oedipus has handed over the rule of Thebes to his sons Eteocles and Polynices but Eteocles refused to share the throne with his brother. Aeschylus' Seven Against Thebes recounts the story of the war which followed. In it, Eteocles and Polynices kill each other.

Tiresias also appears in Sophocles' Antigone. Creon, now king of Thebes, refuses to allow Polynices to be buried. His niece, Antigone, defies the order and is caught; Creon decrees that she is to be buried alive. The gods express their disapproval of Creon's decision through Tiresias, who tells Creon 'the city is sick through your fault.' However, Antigone has already hanged herself rather than be buried alive. When Creon arrives at the tomb where she is to be interred, his son, Haemon who was betrothed to Antigone, attacks Creon and then kills himself. When Creon's wife, Eurydice, is informed of her son and Antigone's deaths, she too takes her own life.

Tiresias and his prophecy are also involved in the story of the Epigoni.